Today the 29th of June 2022 marks the third anniversary of the tragic death of yet another London Black man at the hands of the Metropolitan Police Service whose last words were a premonition of the exact words used by George Floyd a year later “I can’t breathe”

Just to jog your memory on this same day in 2019, the mercurial Lil Naz was breaking the internet with his new country hip hop Old Town Road tune. Donald Trump Jr tweeted and then deleted that the then-Senator Kamala Harris now Vice President wasn’t black because of her Jamaican Indian heritage.

And on the world-famous Coldharbour Lane, Brixton South London a 54-year-old Rasta and reggae musician lay dying on what was slowly suffocating on the hottest day of the year. 54-year-old Black man Ian Taylor died in horrific circumstances surrounded by seven officers on Coldharbour Lane, Brixton, South London.

Lambeth is in a bad way.

Disgracefully, Lambeth in terms of policing has the highest rates of race disproportionality and race complaints in London. We also have one of the highest rates of stop searches, and alarmingly, according to the Met's own figures and Lambeth has the lowest level of Black public trust and confidence of any borough in London.

You’re unlikely to have heard of the case of Ian Taylor after some research I believe the Police, the London and local press and others conspired to ensure that there was, what was in effect, a complete media blackout at the time. The reason for this should be obvious. The Police believed that had the circumstances of Ian’s death been known at the time there would have been public outrage and may have caused widespread civil disturbances if known at the time.

The London Evening Standard reporting at the time said Ian died following a fight. That was a lie

Why was no one briefed?

I have asked a range of senior politicians and some MP’s whether the Met briefed them at the time of Ian’s death in 2019, and all those asked have told me that they knew nothing about this case and they were not briefed by Chief Superintendent Colin Wingrove. I have subsequently written to Mr Wingrove asking for a full audit of precisely who was briefed about Ian’s death at the time. Suffice to say I’m still waiting.

If no elected representative or community representative were briefed, including the Leader of Lambeth local council, local MP’s, and The Mayor's Office by the Met then this represents a most serious subversion of democratic accountability and an attempt by the Met to manipulate the media.

Inhumane treatment.

As a black community, we know that one of the most insidious aspects of institutional racism in policing is that officers view Black people as less than human. Time and time again we see powerful evidence of how the culture of police racism promotes dangerous stereotypes situating any black person as capable of serious violence regardless of age, circumstance, or gender.

The culture of racism is not only malignant it is socially contagious and regularly attempts to rationalise the inexplicable. How many times has a video emerged that shows racist sometimes violent policing where the Met has offered an analysis that bears no resemblance to the real reality we can see on screen? Such is the overwhelming power of racism

That’s why we consistently see policing incident after incident being captured on video.

The truth is that London sees violent arrests of black people daily. The lack of compassion can be witnessed by the sickening abuse of sisters Nichole and Bibba, the brutal treatment of Child Q, and the violent arrest of a 15-year-old schoolgirl in Stockwell recently and it doesn’t stop there.

Wherever a culture of racism exists misogyny and homophobia are never far behind. The cases of Sarah Everard and Stephen Portman provide vivid evidence of the toxic reality of institutional discrimination that is fully established as an informal but all too powerful core cultural value of the Met. It used to be canteen culture, now its mainstream culture.

And these are not isolated incidents, they reflect the reality of institutional racism that leads to the industrial dehumanisation of black people, and because officers know that over the last decade less than 3% of racism complaints against the police were upheld, they act with arrogant impunity These are figures one would expect to see in the despotic regimes of Vladimir Putin’s Russia or Kim Jong-un’s North Korea.

Failure to tackle institutional racism.

Met Commissioners Cressida Dick, her predecessor Bernard Hogan-Howe and Boris Johnson's eight years as Mayor of London's collective failure to tackle racism have been catastrophic. The cumulative effect positively reinforces the racist behaviour of officers, who tend towards using either overwhelming force or underwhelming compassion when dealing with black Londoners.

Whether as victims of crime or suspects the toxic culture means that Black people are rarely believed by police officers. In the Met there exists a powerful culture of doubt and disbelief that drives officers’ behaviour.

Today the sheer scale and depth of this crisis are confirmed with the news that the Met has been put into special measures by Her Majesty’s Inspectorate of Constabulary and Fire and Rescue Services.

A dog would've received better treatment.

Let’s be clear here regarding Ian, a badly injured dog would have been treated with more compassion by these officers. There is no doubt in my mind that had a badly injured dog been found by officers that dog would have received more compassion than Ian received. The dog would have been taken straight to a local vet in a heartbeat, the cold stone reality of this culture of police racism was that Ian was left to die.

Police Bodycam.

Police body cam footage shown at Ian’s recent Inquest shows Ian in handcuffs, lying on the streets telling officers that his airways were closing. Ian was an acute Asthma sufferer and would often need his inhaler to help him breathe. Officers looked for his inhaler but failed to find it they then began mocking and laughing at Ian as he begged for his handcuffs to be taken off and be taken to the hospital.

Ambulance.

Even though the Officers were fully aware that the Ambulance had been delayed they simply refused to take Ian to a nearby hospital. Ian is seen repeatedly begging for his life. On one of the hottest days of the year, in 34-degree heat whilst officers are sharing bottles of water not one of the Officers offered him a drink. At his Inquest dehydration was cited as a contributory cause of death.

He says he's can't breathe....blah, blah blah.

Another police officer can be seen telling his sergeant that Mr Taylor was “playing the old ‘poor me’ card”. Six minutes before Mr Taylor went into cardiac arrest, he reported that Mr Taylor was, “saying he’s got chest pains, he can’t breathe, blah blah blah, it’s all a load of nonsense, but there we go”.

After 25 mins officers moved him out of the sun into the back of a Police car where Ian was told that were no ambulances and that he should grow up. Five minutes later Ian had a massive cardiac arrest, officers gave him CPR, but Ian was declared dead in hospital.

Alliance for Police Accountability. (APA)

As Chair of the soon-to-be-launched Alliance for Police Accountability, we intend to conduct the first national consultation with Black communities in five cities in England and Wales over the next two years. The aim of this consultation is to co-produce a National Black Policing and Anti Violence, Public Health Public Charters that will set out the high-level strategic demands of policing reform and ask the question of what the black community sees as our responsibility to tackle the rise of serious violence.

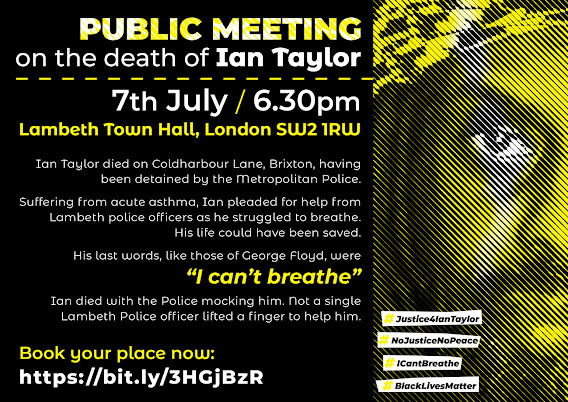

Lambeth meeting.

On Thursday 7th July at 6.30 pmLambeth Assembly Hall, Lambeth Town Hall we will meet to hold Lambeth Police to account for the death of Ian Taylor.

You need to book your place online here in advance.

The meeting will give the community the opportunity to hear the detail of what happened to Ian and you can put your questions directly to Chief Superintendent Colin Wingrove and local Lambeth politicians.

We will also be joined by Marcia Rigg Chair of the United Friends and Family Campaign and sister of Sean Rigg who died in Lambeth police custody in 2008. UFFC is a solidarity and support network of families who have suffered deaths in police and prison custody.

Social media shadow ban protical is full effect.

The information about this event is being suppressed with shadow bans on social media and deep reluctance by anyone other than the Voice Newspaper covering this story. What that means s we need your help to break the silence. Please promote and share articles and share the flyers across your social media.

Use hashtags #Justice4IanTaylor #BlackLivesMatterUK #DeathsInPoliceCustody

Last word...

I leave the last word to Ian Taylor’s Aunt, Pauline Taylor, recounting Ian's last words caught on video:

“‘I need my inhaler…I can’t breathe…I’m dying.’ These were the last pleading words of my nephew. He died on the street begging for help, not from just one, but seven police officers who casually dismissed his pleas and even went so far as to laugh and mock him. What more could he have said in those moments to solicit help and simple humane compassion from those who are sworn to serve and protect.

What has been learnt? One officer said that he would do exactly the same given the same set of circumstances…May God help us! Our family is broken, our pain wakes us each morning and steals into our dreams at night, but in trying to heal we recognise that the disclosures relating to Ian’s untimely and cruel death can be used as a tool to bring about better training, effective practice and holistic awareness and challenge the ugly existence of unbiased racism.”